Sexy parasites - learning activities

Introduction

Introduction

The story about Lisa Ranford-Cartwright's research into the genetics of plasmodium suggests lots of interesting topics for discussion and research.

A good way to generate these is to start with the statements in the news story, and the analysis of these into different statement types.

Learners will have done this already if they've gone through the basic lessons and the follow-up lessons.

If they haven't, here's a copy of our thoughts on the different statement types in the story of Lisa's research.

The rationale for this is described here.

Before we get into the details let's watch a couple of videos:

"Joshua is the very first of a new kind of cat." Selective breeding.

Are you a chimp a cow or a banana? What are genes?

Little class demo of tongue-rolling and maybe banana DNA.

Selected topics

So let's take a look at the statements in this story about Lisa Ranford-Cartwright's research on plasmodium genes. Among others the following look interesting and worth exploring in more detail:

1) Plasmodium gets much more sex than anybody knew, says Dr Lisa Ranford-Cartwright. "They do it all the time."

2) The whole point of sex is to mix one individual's genes with another's.

3) The reason, Lisa explains, lies in the complicated lifecycle of the malaria parasite. "To get from one human to another they have to go through a mosquito," she says.

4) Once in the new host's bloodstream, the plasmodium cells are carried by it to the liver. There they feed, grow and divide many times, before being released back into the blood.

5) If these few dozen plasmodium cells from the mosquito have exactly the same genes as each other, then so too will the new cells in the liver and blood. Like millions upon millions of identical twins.

6) "But my research and other people's has begun to unveil the enormous complexity of parasites in people."

7) It turns out that in countries where malaria is endemic - such as the whole middle part of Africa ...

8) Lisa and her group study this diversity. "We want to know what differences in the genotype  produce important differences in the phenotype."

produce important differences in the phenotype."

9) They do this research by mating plasmodia and studying the results - "just as farmers mate their cows," Lisa says.

10) A plasmodium that multiplies fast in your body makes you much sicker than one that multiplies slowly.

11) Other differences in the plasmodium that make malaria more severe - besides multiplying fast - include the ability to stick in the brain and to infect mosquitoes easily.

12) Lisa's research is aimed at finding all the plasmodium genes that in some way make malaria infections more severe.

13) "If 100 children come into a clinic with malaria, we know that 98 will recover," she says. "But two will get very sick and will have a high chance of dying. Right now we can't tell which two."

14) Finding the plasmodium genes that make malaria severe will allow a quick test on a drop of blood from a child to tell how bad the illness is likely to be.

14) Finding the plasmodium genes that make malaria severe will allow a quick test on a drop of blood from a child to tell how bad the illness is likely to be.

15) Around 250 million people catch malaria every year. Nearly a million of those die. Most are young children.

16) "You think you know what poverty is before you go. But you don't. It's normal to have one child, and sometimes two or three, who have died of malaria."

17) "You remember the long queues of sick people outside the clinics. You remember the children.

18) "What we do is fascinating science. But it's about more than that. It's about saving lives."

Selected topics

Below we've picked out several of these statements, re-ordered them starting roughly with the easiest, and provided extra information and guidance for class activities.

Several contain audio clips of Lisa that tell us more about her and what she's doing - and how she's doing it.

Close to 2000 children aged five and under die of malaria in Africa, every day.

Close to 2000 children aged five and under die of malaria in Africa, every day.

Let's take a look first at malaria around the world, and particularly in Africa, where the vast majority of infected people live.

What we want from you is a short presentation of the problem, with as much detail as possible. Facts and figures. How many people infected, how many deaths, where they are, what's being done, what is not being done.

In your groups prepare an advertisement that gets the facts to people as effectively as possible. It can be in any medium you think works well - audio, video, poster, mobile marketing campaign. You choose.

We want simplicity, clarity and style, as well as facts and figures.

It turns out that in countries where malaria is endemic - such as the whole middle part of Africa ...

Now we want to take a look at what's being done to tackle malaria. One of the commonest statements you'll hear about malaria is that it's a "preventable disease".

But while there is some truth in this, it can be misleading. You might think, "Well if it's preventable why are all these mums and dads letting their children die? They can't be very good parents."

Have a listen to what Lisa has to say about conditions in Africa.

"The reality of people's lives is extremely difficult." Rural Africa

"All you have to do is not get bitten by mosquitoes." Eye-opener

Bed-nets

Bed-nets are often described as the most effective method of prevention of malaria. They keep mosquitoes away from sleeping children and adults.

Take a look for instance at this short UNICEF video and at this one.

So millions of bed-nets are now given to people in Africa every year. But.....

Well what is the "but"? We would like you to tell us.

In your groups please find out as much as you can about bed-nets and how effective they are. You're going to use this information in an activity called Academic Controversy. It's a kind of well-structured debate using cooperative learning.

Here's a summary of the steps in making it work:

Academic controversy

Step 1: Organising information and drawing conclusions

Step 2: Presenting and advocating positions

Step 3: Being challenged by opposing views

Step 4: Conceptual conflict and uncertainty

Step 5: Epistemic curiosity and perspective taking

Step 6: Reconceptualisation, synthesis and integration

And a couple of websites to learn more:

And here are a few websites you could take a look at to research the topic of malaria prevention and bed-nets.

1) There is anecdotal evidence that some people have employed the nets as wedding veils or fishing aids.

2) A treated net costs about $4 - simply too much for many African families.

Mosquito nets can't conquer malaria

Malaria kills. Nets can save lives.

"What we do is fascinating science. But it's about more than that. It's about saving lives."

"What we do is fascinating science. But it's about more than that. It's about saving lives."

Prevention is one way to tackle malaria. The other is trying to cure it using medicines.

Have a listen to Lisa again:

"We have one drug left and that's it. There are no new drugs in the cupboard."

Resistance is the problem. So what exactly is resistance?

In your groups we'd like you to find out please. Once you've done that you have a choice of two methods of presenting what you've discovered.

Take a look at these greeting cards and stickers.

We want something like these from you - visual and effective but with more information. But be careful not to clutter your design with information or it won't work as a card. We do want more science though.

The scientific detail can get complicated but the basic idea is simple. We want you to capture that idea and sell it to people who look at the card or the sticker.

The other presentation method you might want to use for this activity is animation. Take a look at xtranormal or some other online animation tool. Be creative. Here's one we made earlier about the malaria parasite to give you a flavour of what you can do.

A few websites you might look at for researching this activity

Cambodia fights drug-resistant malaria.

Resistant strains emerging to artemisinin.

They do this research by mating plasmodia and studying the results - "just as farmers mate their cows," Lisa says.

Looking back to the activity we did on the statements in Lisa's story, this was one of the few that told us about technology and methods - about how Lisa and her colleagues actually did their research.

So we're going to take a closer look at that in this activity. First let's remember what else we learned about these methods. Here's everything in the story about the methods used in Lisa's research:

They do this research by mating plasmodia and studying the results - "just as farmers mate their cows," Lisa says. "If we have one parasite that multiplies fast, for instance, and another that multiplies slowly, we mate them together and study the offspring.

"Some of these grow fast; some more slowly; some are intermediate. We then look in the genome of these parasites to see which bits are the same in all those that grow at the same rate. In that way we can home in on the genes for fast growth - or any other phenotype we're interested in."

Listening activity

So what do we want to know about this? Let's have another listen to Lisa talking about the methods.

As you're doing so, we'd like you to take a note of every time she says something about what they did. We're looking for "we" or sometimes "you" followed by a verb. Here are a couple of examples to let you see what we're after:

"we take the parasite that grows fast and mate it with"

"you've mapped them, you've identified them"

So here we go:

We are trying to find genes (aims).

We called it GAIL (new finding).

We mate them and look at the offspring (technology).

We're geneticists and we map genes. Mapping the genome (technology)

Let's have some more questions

Take a look please at the list of short statements Lisa made and you've written down, and in your groups come up with three questions, arising from these, that you'd like to put to Lisa on exactly what she and her colleagues did. Since we're looking at the methods and technology she used, those questions are mostly going to start with the word "How".

Once all the groups have their three questions, you should take turns to read them out to the class.

We're now going to whittle these dozen or so questions down to about half a dozen by eliminating duplicates and taking class votes on which ones you want to keep. We're looking for six cracking questions. Your teacher and the Glasgow Science Festival people, when they visit your school, might be able to answer some of your questions. If so we'll replace those with others that they can't.

Further listening, mostly from Lisa

There are lots of phenotypes we're interested in (existing knowledge).

It becomes more complicated when more genes than one are involved (methods background).

Tongue-rolling is not quantitative - you can either do it or you can't. QTL analysis (methods background)

We just found it (new finding)

The proportion of males and females that each parasite produces varies. Sex ratios (aims and applications)

"Isn't that amazing?" Linkage analysis (methods background). Wellcome on genetic markers.

"His computer over-heated and melted his hard drive." It's so good (new finding).

Applications

Applications

Ask Lisa if we can do a demo in the class with this.

Do a demo with a drop of blood.

Want more?

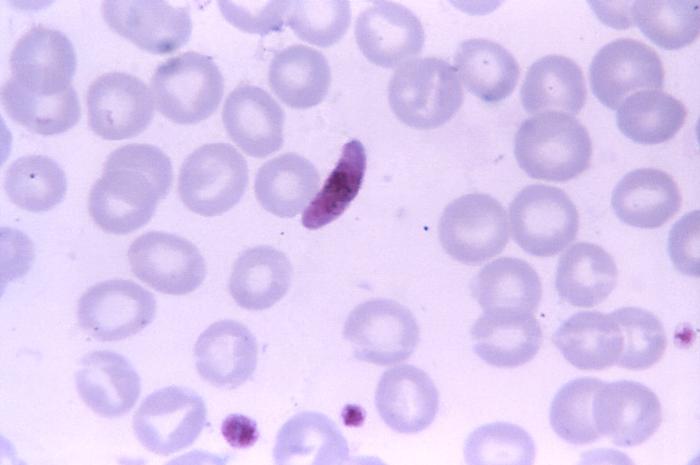

Plasmodium falciparum facts and lifecycle

10 human parasites from New Scientist

Glow Science

How does D\NA make protein?