Toxoplasma - the perfect parasite

There are three people in Markus Meissner's office in the Wellcome Trust Centre for Molecular Parasitology at Glasgow University. So chances are one of us has Toxoplasma gondii living in our body, he says.

1 December 2011

Parasite sex

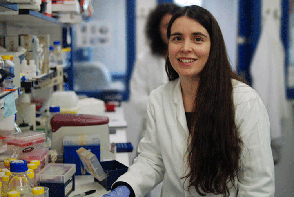

Plasmodium has much more sex than anybody knew, says Dr Lisa Ranford-Cartwright in the Wellcome Trust Centre for Molecular Parasitology at Glasgow University. "They do it all the time. Not all of it is meaningful sex, though. They mate with themselves a lot."

24 November 2011

Wellcome Trust Centre for Gene Regulation and Expression

Biologists now have a complete parts list for the living cell, says Julian Blow, deputy director of the Wellcome Trust Centre for Gene Regulation and Expression But that doesn't mean we understand what's going on. "Molecular biology has made enormous progress. But there's a vast, unexplored territory still out there. To a scientist that's not daunting. It is exciting."

6 April 2011

Epigenetics and Rett Syndrome

Rett Syndrome is a distressing disorder of young girls caused by a faulty gene that fails to produce a protein called MECP2. The protein was discovered by Adrian Bird, director of the Wellcome Trust Centre for Cell Biology. His experiments, aimed at understanding how the protein works, have raised the possibility that Rett Syndrome, and other developmental disorders, might be curable.

4 April 2011

Wellcome Trust Centre for Cell Biology

The inside of a living cell is like central London in the rush hour. The closer scientists look, the more complex life seems. But that won't go on forever, says Adrian Bird, director of the Wellcome Trust Centre for Cell Biology. "Things seem impenetrable when key facts are missing."

29 March 2011

Hypoxia and HIF activation

"My mum likes to hear about my work," says Dr Sonia Rocha, a researcher in the Wellcome Trust Centre for Gene Regulation and Expression. "She isn't a scientist - none of my family are. But they are interested in what I do."

19 March 2011

Doing biology with maths

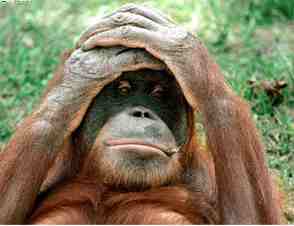

Plenty of people want to bottle-feed orang-utans, but very few can do time-series analysis on orang-utan population dynamics. So if you want to get into conservation and biodiversity learn a little mathematical modelling, says Professor Dan Haydon.

10 January 2011

Myotonic dystrophy

The genetics of the human body are more complex than we ever imagined. But science offers good prospects of treating some genetic diseases in the near future, says Darren Monckton. . Myotonic dystrophy is one of these.

26 November 2010

Immunology in the lab

When Jim Brewer pushes the heavy door open, the vista of gleaming glass and bright lights that meets our eyes seems to stretch to the horizon.

19 November 2010

Immune system dynamics

Why is the immune system like the best Liverpool football sides of the past? No it's not a riddle. It's Paul Garside's analogy for a new window that has opened on our bodies' defence systems and the fight against disease.

18 November 2010

Rehabilitation engineering

Our brains are plastic. This just means that other jobs are found for parts of them that aren't busy. But that's the last thing you want if you're recovering from spinal injury and can't yet move your hands. So Aleksandra Vuckovic is using computers to read thoughts and help patients exercise their brains, until their bodies are ready to move again.

13 November 2010

Amber fossils tell a tale

Insects in amber, perfectly preserved, reveal the movement of continents 50 million years ago.

24 October 2010

Generation IV nuclear reactors

Scientists and engineers are designing new types of nuclear reactor that could be cheaper, greener, safer and more secure than those we have now. But they have plenty of problems to solve, some technical, some financial.

22 October 2010

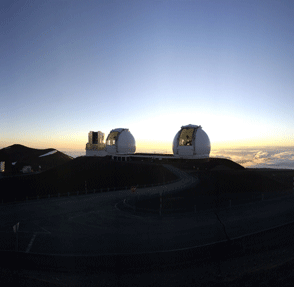

Planet in the Goldilocks Zone

Astronomers have found the first planet in the zone around its star that is neither too hot nor too cold, but just right for life. "Our findings offer a very compelling case for a potentially habitable planet," says Steve Vogt, professor of astronomy and astrophysics at UC Santa Cruz.

1-Oct-2010

Dumpy worm C. elegans

Without connective tissue we would all be a "soup of cells", says Iain Johnstone who is finding out how this complex component of all our bodies keeps us in shape, what goes wrong in diseases such as osteogenesis imperfecta, and how understanding the basic science offers prospects of a cure.

25-Sep-2010

Fighting malaria and trypanosomes

Innovative science means the war against the disease parasites that devastate Africa can be won, says Professor Dave Barry, director of the Wellcome Trust Centre for Molecular Parasitology.

23-Sep-2010

Point of care diagnostics

Point of care is particularly vital in poor countries, says Professor Jon Cooper, where infectious diseases are very common and healthcare systems struggle. But it's also important in the poorer parts of the developed world, where for example thousands of people are dying of TB every year.

21-Sep-2010

Extreme biology

"Thellungiella is a plant that can tolerate cold, high salt concentrations and low levels of nutrients," says Anna Amtmann. "It grows for example in the Yukon in Canada. It is a real tough cookie.”

19-Sep-2010

Cell biology and organelles

"Cells in animals and plants are divided into compartments called organelles," says Nia Bryant. "So we're looking at how the cell determines the make-up of those organelles. This is important for many processes in the body – from producing hormones, such as insulin and adrenalin, to brain function and the firing of neurons.”

17-Sep-2010

Plant circadian clocks

A plant that knows when the sun is going to rise can get itself wide awake and ready to photosynthesise. It can steal a march on its sleepier companions. This is why circadian clocks are found in all higher plants, says Hugh Nimmo, whose experiments have shown that the prevailing wisdom on circadian clocks was wrong.

15-Sep-2010

Meet the scientists

Blue skies, plant clocks and the right marriage partner for a scientist.

20-Aug-2010

Meet the scientists

Dumpy worms to cure disease, sound science for diagnosis and why the war on parasites can be won.

20-Aug-2010

Meet the scientists

Art, science, understanding disease and getting the best out of brain waves at Glasgow University.

20-Aug-2010

Bad newts for builders

Great crested newts are protected by law. So if a builder finds these little amphibians on his land he can't just go ahead and build there. He has to make sure first that the newts are safely moved and found a new home. But how well do the newts do after their translocation? Glasgow University's Debbie McNeill has been investigating.

1-Oct-2009

RoboSalmon

Swimming with wild salmon as they make their last journey upriver to the place of their birth is just one application for a new underwater robot, says Euan McGookin.

14-Dec-2008

Final frontier

Keeping human waste away from drinking water is not glamorous research, admits Bill Sloan - although it can get exciting when you're hunting bugs in the world's wild places.

18-Nov-2008

A rippling yarn

When a team of scientists searching for gravitational waves given off by the Crab Nebula found none at all, they weren't too disappointed, says Glasgow University's Graham Woan. "We would have been ecstatic if we had found them. But we weren't expecting to - and the fact that we didn't tells us a great deal."

30 October 2008

Real science is a fascinating, absorbing, endlessly varied and exciting subject. But school science can seem dull, dusty and irrelevant to some young people.

The topical science stories and teaching resources on this website should ensure that the kids you teach are not among them.

Wellcome Trust Centres

Web 2.0: Cool Tools for Schools

The Science Council

Real Science at Glasgow University

Glasgow Science Festival

Glasgow Science Centre

BIS Science and Society

Enabling inclusive learning

Learning and Teaching Scotland: science

Centauri Dreams

sciencewise

Teachers' Domain

Science teacher resources

Digital Library for Earth System Education

Wellcome Trust news

Science Museum

Ask a biologist

Discovery Education School Resources

BioEthics Education Project: Working with discussion

Science News for Kids

Make it in Scotland

Leon Ray, photographic design

Scotland